VIENNA: The City of the Masters

By JAMES FRANCIS COOKE

Who can ever estimate the contribution of Vienna to the art of music! Who can ever sing the praises of this marvelous city of Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Gluck, and Brahms! At almost every street corner one can see the reasons for its greatness as a musical center. It lies in the public appreciation of music and musicians. With monuments, tablets, and innumerable other ways have the people shown their love for the great tone-art. And this love has by no means died out, leaving only those examples of “petrified sentiment” to tell the tale of Vienna’s former greatness; nor is the love for music confined to the rich; nor is it a mere matter of selfish delight which the people of Vienna desire to keep to themselves. In no city in the world does the popular interest in musical matters seem more general or more intelligent. The citizens seem to take a sort of civic pride in showing its musical landmarks, its wonderful buildings, and its beautiful statues. The present writer can never forget the difficulty he had in finding the way to one of the residences of Beethoven, whither he went to secure certain data. After wandering aimlessly after the directions of an unreliable guide-book, he induced his wife to inquire the way from a young working woman, who was returning from her office for the day. She not only was willing to direct, but persisted in personally conducting the two Americans who wanted to find Beethoven’s former home over a distance of two miles, until finally we came to “Eroica” Place, where many of the master’s greatest works were written. Imagine our chagrin in finding it turned into a brandy distillery!

Who can ever estimate the contribution of Vienna to the art of music! Who can ever sing the praises of this marvelous city of Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Gluck, and Brahms! At almost every street corner one can see the reasons for its greatness as a musical center. It lies in the public appreciation of music and musicians. With monuments, tablets, and innumerable other ways have the people shown their love for the great tone-art. And this love has by no means died out, leaving only those examples of “petrified sentiment” to tell the tale of Vienna’s former greatness; nor is the love for music confined to the rich; nor is it a mere matter of selfish delight which the people of Vienna desire to keep to themselves. In no city in the world does the popular interest in musical matters seem more general or more intelligent. The citizens seem to take a sort of civic pride in showing its musical landmarks, its wonderful buildings, and its beautiful statues. The present writer can never forget the difficulty he had in finding the way to one of the residences of Beethoven, whither he went to secure certain data. After wandering aimlessly after the directions of an unreliable guide-book, he induced his wife to inquire the way from a young working woman, who was returning from her office for the day. She not only was willing to direct, but persisted in personally conducting the two Americans who wanted to find Beethoven’s former home over a distance of two miles, until finally we came to “Eroica” Place, where many of the master’s greatest works were written. Imagine our chagrin in finding it turned into a brandy distillery!

In a little plot in the beautiful cemetery of Vienna there have been erected monuments to commemorate Beethoven, Gluck, Mozart, Schubert, Brahms, and Johann Strauss. The plot is only a few yards square, and some of the composers popularly supposed to be buried there are really buried elsewhere, but the Viennese reserve this little “garden of peace” in order thus to revere their great masters. It is hallowed ground for all musicians, and the Viennese rarely allow the graves to go undecorated with fresh floral wreaths and other remembrances.

Notwithstanding this, musicians generally throughout Europe point to the retrogressive conditions in musical life in Vienna and assure one that the city is in a state of decadence, which unfortunately affects the music as well as the business of the city. With the rate of increase in population falling far behind that of other European cities, there is reason to give credence to this statement. “The Austrian Rome” the Germans are given to calling it, and point to its unsubstantialness. Since this unsettled condition is more than likely to affect the disposition of the American student, it finds a place in this article. In fact, the greatest complaint the writer has heard from music students in Vienna is against the mania of many small tradespeople, waiters, and servants of taking every possible advantage of strangers. In no other German city is one so likely to be annoyed by such constant attempts at petty fraud. Its effect is to make the visitor and foreign resident continually irritated, as nothing so disturbs the average American as the feeling that he is being imposed upon. Many students have assured the writer that they have found this one of the most disagreeable features of student life in Vienna. The better class of Vienna’s residents are the first to deplore this miserable trait. Being obliged to be constantly on the alert to detect imposition certainly destroys the confidence in a manner which only experience can discover. Much of this petty annoyance comes through the double currency, which also, in a sense, makes living in Vienna far more expensive than in Germany, as the monetary unit of the old currency, the gulden, which is retained in general use to a certain extent, although nominally out of currency, is 75 per cent, greater than the German mark. Board, necessities, and luxuries are all considerably higher than in German music centers, and the student with limited means should certainly choose one of the more reasonable German music centers.

One could readily fill the pages of this magazine with a mere outline of the places of historical musical interest in Vienna. In fact, at nearly every turn in the city one is liable to find a relic that seems to demand study and reflection. The new Vienna and the old are sharply contrasted. No finer theater exists than the Burg Theater. In itself it is a masterpiece of architecture and painting that would put to shame many great art galleries. Only a short distance from it are the great Imperial Art Galleries and the Natural History Collection, which rival the museums of the world. The opportunities for correlative study in other branches are most splendid. The grouping of the various great buildings is an architectural marvel. The educational system is one of the most extensive in the world. There are in the city between eight and nine hundred educational institutions, including public schools. The German and Austrian teachers are especially fine, but are much hampered in both Protestant and Catholic schools by the vast amount of time that must be given to theological instruction of an absolutely worthless kind.

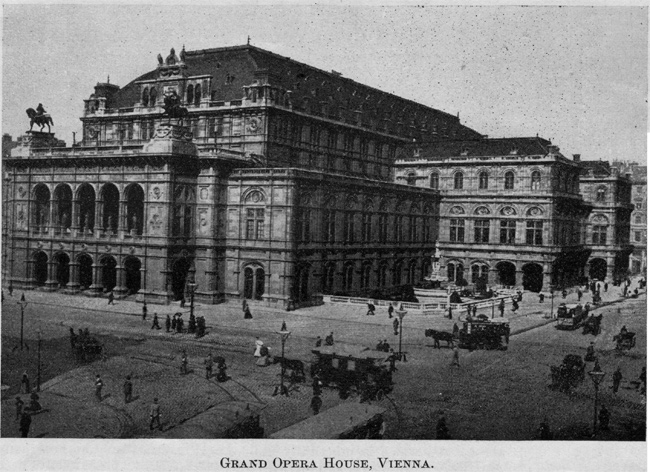

The great Grand Opera House is unquestionably the most important building devoted to music in the city. Though not as large or as ornate as the Paris Grand Opera House it nevertheless covers a large city block and accommodates 2252 people. It cost about six million guldens (about $2,400,000). The performances at this opera house rank with the best given anywhere in the world, and the rates of admission are exceptionally low. The staff of the opera is very great, and the farcical Austrian love for decorations and titles was never more accurately shown than in the year-book of the opera, where the three leading Intendants or Directors of the Opera have no less than eighty spectacular titles to divide among them. What the “Order of the White Elephant of Siam,” which is actually one of the titles, has to do with “Lohengrin” or “Louise” is certainly hard to determine. Aside from these much burdened gentlemen, there are upward of nine hundred other persons connected with this great opera house, including some of the most famous living artists. The industry of the company is astonishing. Over three hundred operas have been given in one week. The writer of this article was fortunate in securing from the Directors of the Opera House, a copy of a list which records the first performances of the operas during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Since the Vienna Opera House has been very progressive, this list is valuable as a record of the status of operatic work in the Austrian capital. The number of unfamiliar titles in it is a fair indication of the unusual opportunities offered to the student to hear rare works. No European city offers superior advantages in this direction.1

After the world-famed Grand Opera, next in musical interest for American students, comes the Gesellschaft fur Musik-Freunde (Society for Friends of Music, founded in 1817) and its great conservatorium, which possesses one of the five first-class conservatory buildings in Europe, to wit, Berlin, London (Royal College), Leipzig, Frankfurt, and Vienna. In size and elegance it is second only to the magnificent new High School in Berlin. It possesses one of the largest conservatory libraries in Europe and one of the finest conservatory museums. The Society of Friends of Music, which also provides for an annual series of unexcelled orchestral and choral concerts, has had as conductors no less personages than Rubinstein, Brahms, and Pauer. The hall in the conservatory building is one of the finest of its kind. In fact, the entire building is admirably planned. The teaching rooms are large, airy, and light, and the pianos are far superior to those found in many other far-famed conservatories. The school points with pride to its pupils, Goldmark, Ernst, Richter, Joachim, Mottl, and many other illustrious musicians. Its teaching staff is uniformly splendid, a single instance being the engagement of such a master as Emil Sauer as Professor of Piano. Its corps of instructors numbers over 50 prominent musicians, and its students upward of 1000. As in most conservatories, by far the greatest number of students are piano students, there being during the year 1901 over 360 piano students and 11 students in the so- called “Meisterschule für Clavier,” which is a school for “virtuosi” under the direction of prominent virtuosi. Next in importance to the piano department is the theoretic department, and, closely following, the vocal department.

After the world-famed Grand Opera, next in musical interest for American students, comes the Gesellschaft fur Musik-Freunde (Society for Friends of Music, founded in 1817) and its great conservatorium, which possesses one of the five first-class conservatory buildings in Europe, to wit, Berlin, London (Royal College), Leipzig, Frankfurt, and Vienna. In size and elegance it is second only to the magnificent new High School in Berlin. It possesses one of the largest conservatory libraries in Europe and one of the finest conservatory museums. The Society of Friends of Music, which also provides for an annual series of unexcelled orchestral and choral concerts, has had as conductors no less personages than Rubinstein, Brahms, and Pauer. The hall in the conservatory building is one of the finest of its kind. In fact, the entire building is admirably planned. The teaching rooms are large, airy, and light, and the pianos are far superior to those found in many other far-famed conservatories. The school points with pride to its pupils, Goldmark, Ernst, Richter, Joachim, Mottl, and many other illustrious musicians. Its teaching staff is uniformly splendid, a single instance being the engagement of such a master as Emil Sauer as Professor of Piano. Its corps of instructors numbers over 50 prominent musicians, and its students upward of 1000. As in most conservatories, by far the greatest number of students are piano students, there being during the year 1901 over 360 piano students and 11 students in the so- called “Meisterschule für Clavier,” which is a school for “virtuosi” under the direction of prominent virtuosi. Next in importance to the piano department is the theoretic department, and, closely following, the vocal department.

There is also in connection with the school a department for the training of teachers of voice and piano. The 26 students in this department during the year 1901 were entitled to 417 lessons, which were divided as follows:—

General Pedagogy, 43 lessons; Special Musical Educational Theory, 81 lessons; Methods of Instruction, 104 lessons; Piano Literature, 60 lessons; History of Music, 160 lessons; Esthetics, 44 lessons; Acoustics, 68 lessons; Instrumental Knowledge, 25 lessons.

Thus may we see what attention is given to the correlative training of music teachers in this great conservatory. The list is one of the best the author has collected in Europe. Other similar schools lay greater importance upon piano literature and give many more hours to the study.

The number of free and partial scholarships is astonishing, and during one year one of six partial scholarships was awarded to an American, a very unusual distinction from a foreign music school, restricted as they usually are in this matter, to native-born students. The enormous work of the conservatory is almost unbelievable. In one year over 116,700 lessons were given. In 1901 upward of 40 concerts, recitals, and operatic performances were given by the students. One program of the Virtuoso School for Pianists under Emil Sauer was, for instance:—

J. N. Hummel ……………… Clavier Concerto, B Minor

Schubert-Tausig ……………… Military March

Chopin ……………… Impromptu, Op. 36

Beethoven ……………… Sonata, Op. 110

Saint-Saëns ……………… Clavier Concerto, No. 4, Op. 44

F. Liszt ……………… Mephisto Waltzes, No. 1

In the Opera Department parts of the following operas have been given publicly during a single year by the students: Il Trovatore, Der Widerpfänstigen, Zälmung, Die Zauberflöte, Die Afrikanerin, Faust, Das Glöckchen des Eremiten, Martha, Die Hugenotten, Fra Diavolo, The Daughter of the Regiment, Hamlet, Tannhäuser, Aïda, La Sonnambula, Carmen, Hans Heiling, The Flying Dutchman, Romeo and Juliet, Cavalleria Rusticana, Lucia di Lammermoor, La Favorita, Das Heúnchen am Herde, Fidelio, Die Hochzeit des Figaro, Lohengrin, Mignon, Traviata, L’Africaine, The Prophet, I’Pagliacci, Die Weise Dame, The Masked Ball, Die Verkaufte Braut, Hansel and Gretel, Elisir d’Amore, Werther, and Der Wildschütz. It would be difficult to imagine a more comprehensive list. It is far more extensive than any one of several dozen similar lists the writer has secured from other European conservatories.

So much has been written and said about the work of Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna that the musical public is very familiar with almost every phase of it. Any further reference to it would be obviously out of place in this article. Leschetizky doubtless attracts more American students to Vienna than does the conservatory with its unquestionably fine staff. Not since the time of Czerny has Vienna possessed such a successful teacher. The traditions of the famous Czerny are possessed by the still greater Leschetizky, who was himself a pupil of Czerny. A close observer of Leschetizky’s fundamental work will discover that it differs little in subject matter from the orthodox exercises that have been given for years by disciples of the Viennese school of piano playing, the difference being in the method of teaching the exercises and not in the exercises themselves. A city’s musical prestige lies not in its past, but in its living masters. Leschetizky retains for Vienna much of the city’s former prestige. Unless some great master arrives to succeed him the city must eventually fall far behind the other more progressive and aggressive German music centers—Berlin, Munich, and Leipzig. After all, it is not in the matter of superior instruction that all German centers excel American centers, for it has frequently been proven that American students have actually accomplished much more in a shorter time in America than other students equally talented have accomplished abroad. The great claim of Continental cities lies in the almost endless opportunities for hearing music of all classes. The average American operagoer rarely has an opportunity of hearing more than 15 per cent. of the list referred to previously. In fact, a well-read musician in New York, to whom I showed this list, had never heard of more than 40 per cent. of the operas. These unknown operas are by no means all fiascos. Take, for instance, Charpentiers’ “Louise,” which has had such exceptional success abroad and which is practically unknown as yet in America. As in opera, so is it with all other classes of music; the opportunities for hearing new works seem unlimited, and herein lies the greatest advantage of Europe over our own country.

1 The list to which Mr. Cooke refers contains the names of over two hundred operas, with dates of first performances. The Editor regrets that lack of space prevents the printing of the list.