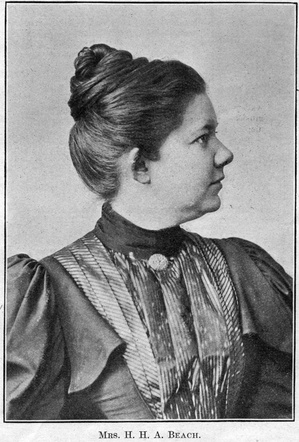

A TALK WITH Mrs. H. H. A. BEACH

Reported by WILLIAM ARMSTRONG

When Mr. George Whitfield Chadwick first heard Mrs. Beach’s symphony, “Gaelic” he is said to have exclaimed:

“Why was not I born a woman?” It was the delicacy of thought and finish in her musical expression that had struck him, an expression of true womanliness, absolute in its sincerity. The high intelligence and grasp of treatment on the technical side are just as pronounced.

The Personality of Mrs. Beach.

The Personality of Mrs. Beach.

Of foreign women composers far less gifted a deal has been written in America. That which we know of Mrs. H. H. A. Beach comes mainly through the medium of legitimate criticism. Of her personality and her thought on subjects bearing on her art little has been said. In one sense this is the better, for her reputation has been built on the excellent foundation of her work. The theatrical and picturesque side that has gained for certain French women composers a degree of standing because they are women quite as much, perhaps more, than because they are writers, has in her case been fortunately escaped. The situation is logical, as far as she herself is concerned, for Mrs. Beach is much too able and too sincere to be in danger of the fantastic treatment which is the portion of the poseur.

She is a woman of charmingly simple manners, and, as foregone conclusion, of high, innate refinement. She is of medium height. Her eyes are of a grayish blue, large, and smiling. Her complexion is fresh and brilliant. Her blonde hair, primly parted, is brushed back smoothly from her face. The manner of her wearing of it, and the quaint style of her dress, rather that of the early seventies than of to-day, make her appear, through choice, so much older than she in reality is that you recall certain figures in comedies that assume middle age in the first act, and blossom into full youth in the second with a ten minutes’ drop of the curtain between.

Her straightforwardness is like her personality—gentle, direct, convincing. You can fancy people with oblique moral vision hurrying back into the hall after meeting her, to leave their insincerity with their overshoes.

If you should put the direct questions to her as I did you would learn that she composes when she feels the inclination move her to it; that she studies the piano when she is not writing; that one time of the day is as good to work in as another, and that her housekeeping is of a very earnest interest to her. This last, however, was an admission, not an answer; but there was such ample proof of it that it must be put down. So many great ladies in art have told me what good housekeepers they were, and, after leaving them, I have had to stop, on turning the first shielding corner, to brush from my overcoat the veneer of dust it had acquired on their hall bench. Mrs. Beach’s domestic regime is not of this type. It fills you with chagrin, indeed, not at the prospect of dust carried out, but at the fearful possibilities of dust carried in.

That especial afternoon at Mrs. Beach’s Boston home, in Commonwealth Avenue, the theme wandered presently to the literature of the pianoforte. In the main it turned upon the many things by classical composers that people never thing (sic) of playing, gems in their way, but crowded from sight by others by those same composers, which are made hackneyed and familiar because every pianist takes a turn at them.

Seek Out the Good but Less-known Works.

“There is a new field in the old classics,” said Mrs. Beach, coming straight to the point; “minor works, not so great as the more familiar ones, perhaps, but bearing the unmistakable autograph of the master. The very reason that so many stay away from recitals by modern virtuosi is that they, with small exception, play the identical things. The credit must be done Harold Bauer that he is one who does not follow the stereotyped program plan. His recitals are always enjoyable. Some others must be numbered with him in this search after originality, but they are few, not many. And on this very point, identity in the matter of selection, how the less gifted challenge comparison with the truly great by playing the same familiar compositions. As far as the piano student is concerned, the teacher is apt to give what the pupil likes, what is popular at the moment. I do not mean to cast any reflections on the conscientious, hard-working teacher; I do him or her all honor and credit. In this matter of a selection of the familiar the pupil is prone to be led away by enthusiasm for some composition that he has heard given an extraordinary performance, and it will doubtless do him good to study it. But it is well to combine an admiration of the unknown as well as of the new in the dear old classics.

Thus You Develop Individuality.

“Hunt up the lesser known things as well as those that are representative. What I say is more as a suggestion to the pupil than a blame for the teacher. Take the less-known sonatas of Beethoven; take Bach’s complete works, the little fugues and things, fresh and unhackneyed; they present so many beauties. In studying them, free from an imitation or composite of imitations in interpretation that pursues you in studying familiar things, you are thrown on your own thought and ideas. You are developing your own originality or individuality as the case may be. Beside this you are broadening your knowledge of the literature of your instrument and of the thought of its masters.

“The pupil who will give extra time to it may spend years in the old classics. Philipp Emanuel Bach, Graun, Padre Martini, and as far back as Couperin and Rameau, present little old precious bits for the home and the musical growth. There are so many good editions of them by men of note, or arrangements transcribed just enough to be of use to the pupil of to-day.

Gems, Not Well Known, that May be Played.

“Among the unfamiliar in pianoforte literature are some of the Schubert impromptus, exquisite gems that are never heard; the one in C major is phenomenally beautiful. His sonatas I recommend, oh, so heartily; if not the entire work, a movement here and there. The great one in B-flat is my favorite.

“Again, there are the lesser mazurkas of Chopin, smaller things not given by the virtuosi, and they come with an almost absolute sense of novelty. The smaller things of Schumann we never hear, and yet they present a mine to the student.

“I love some things of Mendelssohn. The ‘Songs Without Words’ I am fond of playing, not the better known ones, but a little group of six or eight of those that are passed by for others grown more familiar through public performance. His preludes and fugues are exceedingly fine, and to be recommended to the student. The fugue form he has grasped with a wonderful insight.

“Liszt’s Consolations,’ his ‘Rossignol,’ his valse in A-flat; and of his transcriptions of the Schubert waltzes, best of all the one in A major, and his sonatas and larger works make further items of interest.

Von Bulow’s Program Methods.

“Von Bülow knew and appreciated the value of including in his programs the little-known works of well-known composers, and there was always in his recitals an added charm of novelty. I remember that when he played for the last time in Boston he gave some Beethoven sonatas that are seldom heard, the Chopin ‘Variations’ and ‘Allegro de Concert,’ that I have never heard before or since, and some fresh things by Schubert that I remember particularly. With his beautiful interpretations of the classics, so scholarly and interesting, he knew so well the value of research and of presenting the unfamiliar.

“There was one afternoon that I recall especially when he transposed several of his numbers with such a roguish air. The Chopin ‘Tarantelle’ in A-flat he played in B major, and it was infinitely more brilliant; the ‘Impromptu’ in G he played in G-flat, and it was more poetic. I do not believe that he did this on the spur of the moment, but to secure his effects, trusting to the chance that it would not be noticed. And for the matter of that the critics, apparently, had no inkling of it, for the fact was not alluded to by one of them at the time. But what a comical air von Bülow assumed when he was busy with it.

The Music of To-day.

“I do not deprecate the study of the music of today; it belongs to the time, like its painting and literature, and it brings us more securely by contrast to the hidden beauties of the old composers. In a contrast of contemporary painting and literature with music I see no ground for discouragement. How many pictures are painted; but how few, comparatively, are of an absolute greatness. How many books are written; thousands annually, but how few survive.

“Much of the contemporary piano music of the better class is evanescent; we hear it to-day and never again. There are more good songs than piano pieces; tons are turned from the presses every year, but the value is small in proportion to the output. On the other hand, pictures are painted by the thousand, and novels as many in number are given forth in months, and the results are no better.

“Some of the Russian pianoforte music is interesting, but a great deal of it, as we hear it, is light and superficial. Occasionally, however, there are compositions of great beauty. The Russian songs and orchestral music are stronger but it is not so easy to get good music for the piano.

Value of Ensemble Playing.

“Brahms, next to Bach and Beethoven, gives me the greatest happiness. With this mention of Brahms comes an important item of consideration to the pianist, and that is the enormous value to him of four-hand arrangements of chamber and orchestral music. The literature of the piano is not all that the piano student requires; he must go outside of it to complete his equipment. It is of great value to him to study chamber and orchestral music in these arrangements. He gets the beauty of it by this means, all but the coloring. He learns to understand it, and that is a great thing. He knows the drawing, as it were, by this method, and when he hears it presented in the original form he hears a familiar friend. All of Brahms’ chamber and orchestral works may be had in these four-hand arrangements.

“In the evenings and at leisure moments the student can become acquainted with the overtures, quartets, and symphonies of the old masters. Many quartets, even under the most favorable conditions, cannot be heard in performance on stringed instruments oftener than once in four years. Many Mozart and Haydn symphonies do not find a place in orchestral programs at all. The great later Beethoven quartets, so difficult of understanding to the versed musician, are by this method of four-hand performance brought to a nearer acquaintance. Liszt’s transcriptions of Mendelssohn and Mozart and even of Beethoven’s ‘Ninth Symphony’ are most valuable and enlightening.

“The literature of the piano is, indeed, not all that the piano student needs. He must go outside of it, especially when unable to hear other versions of chamber and orchestral music.

“Discrimination must stand us in good stead to distinguish between the particular kind of sonatas to put on a program for home performance and for concert. Many think only of the biggest, or of what they have heard some one else play. But there are smaller pearls with the impress of the master hand on them.

“Respect the old masters, but not only by playing the known ones of their works.”