No study could be better calculated to develop strength and independence of the forearm and wrist than the eighth Caprice. It should be played in the upper quarter of the bow, and in the following manner:

The upper arm should take no active part in the work, though it is obviously impossible for it to remain motionless. The wrist must remain supple throughout the entire study. The forearm necessarily responds to every movement of the wrist, but it is the latter that must do the actual work.

In my edition there is nothing indicated at the beginning of this Caprice to guide the player regarding the desired quantity of tone. It should unquestionably be begun forte. Later on, also, there is a careless employment of the forte which perplexes the majority of players. The fp in the 6th measure is correct, but the forte must be resumed in the following measure. The last two measures should be played leggiero.

The Ninth Caprice.

The Adagio of this Caprice, like all of Rode’s slow movements, abounds in opportunities for the display of beautiful violin-playing. The tempo mark in my edition, 84 eighths, is excellently chosen.

The second measure often betrays a habit which is exceedingly inartistic, affecting, as it always does, the player’s style and general bowing. I allude to the up-bow on the third beat of the measure. Most pupils resume the stroke at, or about, the point of discontinuance on the previous note. Such a habit naturally precludes the possibility of a broad style, and contributes materially to a feeble and uncertain manner of bowing. The up-stroke, on the dotted eighth note, should be re-begun at the point of the bow.

The ornamentation on the first quarter of the third measure sometimes disturbs the pupil’s sense of rhythm. The group should be played in such manner as not to disturb, in the least degree, the time-value of the sixteenth note (A).

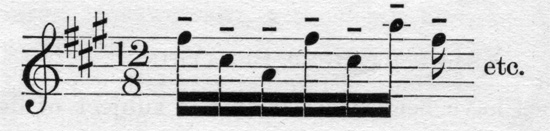

The pupil should not be mislead by the following group on the last eighth of the first measure:

The general tendency is to linger on the upper note (B): a misapprehension which destroys the musical meaning of the whole phrase. The first quarter of the sixth measure is manifestly the musical resting-point.

The general tendency is to linger on the upper note (B): a misapprehension which destroys the musical meaning of the whole phrase. The first quarter of the sixth measure is manifestly the musical resting-point.

The Allegretto is a severe tax on the wrist. The bow must remain on the strings, and all notes that are not slurred must be sharply detached from one another. In the eighth measure

it is advisable to use at least half of the bow on F-sharp, in order to obtain sufficient freedom of stroke on the B. The same principle applies to the 10th measure.

it is advisable to use at least half of the bow on F-sharp, in order to obtain sufficient freedom of stroke on the B. The same principle applies to the 10th measure.

In studies of this character the pupil will always find it difficult to adhere to the tempo, the tendency being to increase the speed rather than to diminish it.

The Tenth Caprice.

There is scarcely anything in this study that calls for analytical comment. In the class-room much can be said and demonstrated regarding its peculiar worth and difficulty; but written words, wholly unaccompanied by demonstration, are obviously inadequate for a study of this nature.

It will be seen that the purpose of this study resembles that of the eighth Caprice, and that in design, also, there is a striking similarity. It should be played in the upper part of the bow, with independent forearm and flexible wrist.

Its demands on the musical intelligence of the player are insignificant. All dynamics, however, must be rigidly observed, and the player must aim at maintaining a fine quality of tone.

The Eleventh Caprice.

This study is written in Rode’s happiest vein. To the average player it may seem to be calculated merely for the technical development of the fingers and the wrist; but a close study of its general design reveals the fact that, in this Caprice, Rode has artistically combined many valuable features of the higher art of violin-playing.

The proper division of the bow, in the 6th measure, causes the majority of pupils some difficulty. Their perplexity is occasioned chiefly by the groups of detached notes in the previous measure. These must naturally be played at the point, which leaves the player with an insufficient amount of bow for the sextoles of the 6th measure. This difficulty is obviated, however, in the following simple manner: the bow should be pushed quite rapidly on the first note of the 6th measure, so that fully a fourth of its length is utilized. This will give the player sufficient freedom for the down-stroke, after which it will be possible for him to employ the entire length of the bow for the remaining sextoles.

The 8th measure should be played as follows:

Too often there is a strong tendency to cramp the bowing in the 23d measure and in all subsequent measures of similar construction. Not only must the utmost flexibility of the wrist be maintained, but the pupil should employ a sufficient amount of bow to avoid angularity of style.

Too often there is a strong tendency to cramp the bowing in the 23d measure and in all subsequent measures of similar construction. Not only must the utmost flexibility of the wrist be maintained, but the pupil should employ a sufficient amount of bow to avoid angularity of style.

The modulation to D major (30th measure) may legitimately be preceded by a slight ritenuto; and the whole episode, beginning with the 30th and ending with the 33d measure, requires suave, graceful playing rather than metronome-like precision. What follows, however, demands the resumption of a vigorous style.

The octave progressions, in the 59th and 60th measures, point a much-needed warning to most pupils. Though the composer has plainly indicated that the accent should fall on the lower note of the octave, most players have the habit of disregarding this accent, giving the upper note the prominence which the lower one should receive.

In my edition the 70th measure is grouped as follows:

The bowing given below is certainly more difficult, but the result is proportionally more artistic.

The bowing given below is certainly more difficult, but the result is proportionally more artistic.

Again, in the 78th and subsequent measures the pupil must be careful to accent the lowest note. (To be continued.)

Again, in the 78th and subsequent measures the pupil must be careful to accent the lowest note. (To be continued.)