[Note : This is the first of a series of talks with prominent artists which Mr. William Armstrong, the well-known critic and writer, has obtained for The Etude. The next will be “The Study of the German Song,” by Mme. Schumann-Heink, to be followed by M. Pol Plancon on “The Study of the French Song,” and Mme. Lillian Nordica on “Woman in Music,” particularly addressed to the American girl music student.—Ed.]

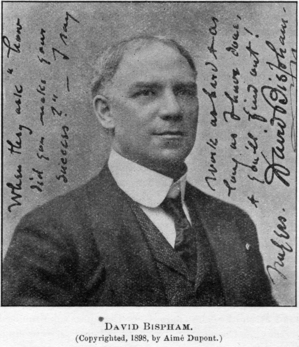

It was at the Players’ Club one sunny afternoon that Mr. David Bispham gave me, for the readers of The Etude, his ideas on the English song and many interesting points bearing upon the singing of it. His close identification with music in London gives Mr. Bispham a unique place among native American singers. This aspect of conditions is heightened by the fact that few American men have won universal recognition as singers as compared with American women.

All this was not accomplished by Mr. Bispham without the struggle that is as necessary to the broadening of the man as it is to the broadening of his art. From a New Jersey farm to the position of one of the foremost baritones of London, and the consequent recognition that it brings, is a far cry, and this is what he has accomplished. After a college education Mr. Bispham was destined for a business career. “But there seemed other things,” said the singer, with a broad smile at recollection of his experiences, “for which I seemed to have more talent.”

All this was not accomplished by Mr. Bispham without the struggle that is as necessary to the broadening of the man as it is to the broadening of his art. From a New Jersey farm to the position of one of the foremost baritones of London, and the consequent recognition that it brings, is a far cry, and this is what he has accomplished. After a college education Mr. Bispham was destined for a business career. “But there seemed other things,” said the singer, with a broad smile at recollection of his experiences, “for which I seemed to have more talent.”

Recognizing this, he devoted himself to music, not knowing the struggle ahead, a struggle which has made him caution many a young singer to think well before he enters upon the same career. Whether we happen to be singers or not, to hear from a successful man the factors that he considers as having helped to his success must be of interest, for, after all, certain traits of mind and method are identical with success in every branch of art.

The surroundings that afternoon were particularly calculated to a congenial talk. It was in the library of the Players’ Club, Edwin Booth’s old home, a large room, subdued in colorings and filled with many mementos of the great actor and the past with which he was identified. In keeping with the surroundings was Mr. Bispham’s manner. There was the air of artistic repose about him which assured one that, whether he finished talking on the subject in hand to-day or whether the conversation should last well into to-morrow, it was quite the same. His desire was to bring out all the thoughts he had upon the points in question. He is a man who does only one thing at a time, and concentrates all his energies while he is doing it. After all, the glimpse he allowed me of himself in this particular may give a clearer idea of the reason for his success than anything he told me in words. It is only the verification of a wisdom older than the hills, “Whatsoever thy hands find to do, do it with all thy might.”

* * *

“First of all,” said Mr. Bispham, “in studying a song in English or in studying a song in any language the thing is to find out what it is all about. We must know what it means. I do not recite the words over alone. It might be a good plan to do it, but I have, somehow, not found it necessary. I read over the words first, then the music of the song with the words. After that I study the two always together.

“The same verses have been set to music by many composers, and no two have interpreted them from the same point of view. Schubert, Franz, Beethoven, have in cases chosen the same words and one has been more successful than the other. The ‘Nur Wer Die Sehnsucht Kennt’ of Tschaikowsky, for instance, is far superior to Beethoven’s setting of the same words. Rubinstein’s setting of ‘Thou Art So Like a Flower’ is, perhaps, not better than Schumann’s. The thing is for the singer to select that setting of a song which appeals to him most strongly. One who would make a success with Loewe’s ‘Erl King’ would likely fail in Schubert’s song to the same words. So it resolves itself not alone into the understanding of the words, but also the suitability to us, as individual singers, of the style of setting given, quite apart from the necessary consideration of range. It depends upon the singer whether he makes the ‘Erl King’ of Loewe more effective than Schubert’s. He must get at the true inwardness of the song as it is written.

“Some one asked Sir Joshua Reynolds what he mixed his paints with. ‘I mix them with brains, sir,’ was his reply. The great thing is always to choose songs with intelligence. I endeavored always to have something new, to have the modern represented in my program. In a recent recital I sang a group of songs still in manuscript. Some of the critics said those songs were unworthy to be placed with the rest, yet of those five songs two were redemanded by the audience, and the next day the composer had two offers from publishers. Here, again, comes a most important thing for the singer to consider: the making of his program. Always be careful what songs you place together. I have seen some very beautiful selections of songs put together so thoughtlessly that the effect was that of a fine picture ruined by some sudden dash of inappropriate color.

“Take the old songs of Dibdin and Shields. None has ever set these verses to music except themselves, because they were the product of a certain style and way of thought of the moment. You find the older singers give them in a style that to us seems exaggerated, and yet that style belongs to the time. Sims Reeves, connected with the past, sang them in this way, as did Edward Lloyd and Ben. Davies who followed him, because it is the way to sing them. Mr. Richard Mansfield sang to me ‘She Wore a Wreath of Roses,’ a beautiful old song, and he sang it with those same exaggerations. On questioning him he assured me that it was the way his mother, Madame Rudersdorf, sang it, and as the traditions demanded.

“Turn again to such beautiful, simple old songs as ‘Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes.’ It would seem as though there was only one way to sing it—with simplicity. But sing it strongly, for it is a song of strength as well as simplicity. Above all, in such a song as this give absolute attention to rhythm, not taking liberties. Oh, that is where so many singers make a mistake! They think to put their own individuality into a song by exaggerating the rhythm of it. It is simplicity that is so hard to attain in any art, and in singing more than any other. And so I have found that little gem, ‘Oh, so Sweet is She,’ the melody of which is anonymous and preserved in the British Museum. It has the most exquisite sentiment which is purity itself, and makes strange contrast with some songs that are sung in England to-day. After all, it is the hardest songs that are easiest to sing, and these little songs, because of their very simplicity, are the most difficult. Of late a number of these charming old melodies have been set to modern accompaniments, and thus preserved. Some of these have been well done by A. L., the mother of Liza Lehmann, and who has a valuable collection of old melodies.

“Villiers Stanford I place at the top of the British song-composers, not so much through the things he has written himself, but for those old melodies that he has arranged and preserved, old Welsh, English, and Irish melodies, the last so full of a quaint humor. These, again, are to be sung with great simplicity of style.

“The rendering of the song depends so much upon the individual. He must always have command of himself, as an actor would do even in the most moving moments. The instant that he gives way he drops into sentimentality through excess of emotion. Feel deeply, but have your feelings under command, for in the moment that you lose your self-control you lose also your hold upon your audience.

“Again, take the old songs of Henry Purcell. Some of them are tremendously difficult. That mad song of his, ‘I’ll Sail Upon the Dog-Star,’ is one that has required great thought. In the study of this, as in the study of all songs, I take the difficult phrases out and try the breathing in different ways, so as to give them in the most effective manner.

“I asked Edward German, who has written a great deal for orchestra and few songs, why he did not give us something in this latter branch of composition; his reply was that he felt his melodies instrumental, not vocal. My retort was that he might write some of his instrumental melodies for the voice, that I thought they sang well. He acted upon the suggestion, and has gotten out a charming volume.

“Sir Hubert Parry has a marvelous facility in composition. ‘Job’ is his best work, as far as I know. Then, too, in the field of song-writing there must be mentioned among the British contemporary composers of eminence Sir Alexander Mackenzie, Arthur Hervey (a most able composer), Elgar, Somervell (whose songs I have sung in America), and the talented Clarence Lucas. With the British concert public there is steady and gratifying elevation in the field of the songs.

“And here we come to an important question: Is English a good language to sing? My reply is that the only English that is bad to sing is bad English. The English language is as noble and as singable as any other language.

“As far as singing the songs of German, French, or other composers in English translations is concerned, there is this to be taken into consideration: the composer, having thought of the music through the medium of his own language, certain phrases are adapted to the poem he has selected. But if a good translation can be obtained there is no reason that it should not be sung.

“In the rendering of a song as much depends upon the singer as does upon the actor in a play.

“My uncle, William Bispham, closely associated with Edwin Booth, told me that one night he went with Thomas Bailey Aldrich to the great actor’s dressing-room to congratulate him on his brilliant rendering of some poetic part. They found him sitting in front of his dressing-table, his head bowed on his arms, the picture of despair. He told them that he felt he could never act again, that he was in despair over himself because he had acted so badly. The house had been wild with enthusiasm.

“On another occasion they went to Mr. Booth to beg him to play up a bit, they felt he was not doing as well as he might. They found him in the gayest of spirits. He said that he felt that he had never done better, and was rather indignant at their suggestion.

“So it is with the singer and his songs. Recognizing that this is the ease, all a singer can do is to do his best at the time, to give full value to notes and words. It will have a certain effect. There are moments when one rises above one’s ordinary plane and brings out the value of the composition as never before. Then comes the difficulty to live up to that. Leave nothing to chance or to the mood, which will play a separate part to itself. Study things so thoroughly that you cannot do them badly. If that method is pursued one may be even in bad voice and the art of singing comes and helps one out of the difficulties.

“This being in bad voice is oftener than not a matter of digestion, and not of the voice at all. If one would sing well the last meal should be taken four hours before singing, and, in cases of unusually trying demand, four hours and a half before singing. I have myself found upon occasion that I did not seem in good voice, while in reality I knew that my voice should be in good condition. The trouble could be traced simply to the matter of digestion. The vocal chords were affected and the very muscles needed called into play by other causes.

“The singer must always be ready to struggle against fatigue and unpleasant occurrences by forgetting himself through interest in his song and its interpretation. Recently I had a contretemps of my own at Washington of which more than the correct version has been given.

“In the hurry of packing, the waistcoat of my evening clothes was left in New York. When I made a late discovery I confided my trouble to a lady at whose house I had been entertained, and a gentleman kindly came to the rescue on her suggestion.

“One of the versions published was that I borrowed a waistcoat from a waiter and had it pinned on me. Graphic descriptions followed of how, at critical moments in the song, I was made aware of the critical presence of the pins.

“To tell the truth, I was very far from comfortable, although the waistcoat was ripped at the back, and I have passed many happier moments than the ones I sang in it. But I thought to myself that that was one of the times when one’s art had to be invoked, and I invoked mine very hard. After the first number I began to feel more at ease. By the end of the evening I had my audience with me, and was asked at the close of the program to come back again this season.

“My song had put thought of self completely out of my mind, that was all.”