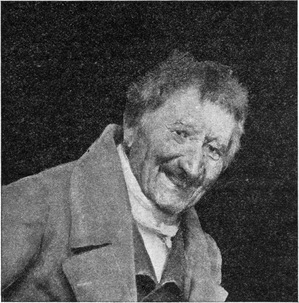

I may not be handsome but I have a kind face, have I not? So many letters were forwarded me by my editor asking for my autograph, photograph, and opinion of Mother Snigel’s Cough Syrup, that I decided to take the bull by the horns and publish my portrait at the head of these columns. You may observe—that is if you are a reader of the human countenance—that my features are more amiable than my pen but that my pen is mightier than my smile. This may sound vain but then vanity in an elderly person is pardonable; hence these preludings.

I may not be handsome but I have a kind face, have I not? So many letters were forwarded me by my editor asking for my autograph, photograph, and opinion of Mother Snigel’s Cough Syrup, that I decided to take the bull by the horns and publish my portrait at the head of these columns. You may observe—that is if you are a reader of the human countenance—that my features are more amiable than my pen but that my pen is mightier than my smile. This may sound vain but then vanity in an elderly person is pardonable; hence these preludings.Where did I leave off? Oh, yes, at Clementi-Villa-on-the-Wissahickon. Well, I am still there and mean to stay until the snow drives me to that uncomfortable aggregation of villages, called a city. Have you read Thoreau’s “Walden” with its smell of the woods and its ozone-permeated pages? I recommend the book to all pianists, especially to those pianists who hug the house, practising all day and laboring under the delusion that they are developing their individuality. Singular thing, this rage for culture nowadays, among musicians! They have been admonished so often in print and private that their ignorance is not blissful, indeed it is baneful, that these ambitious ladies and gentlemen rush off to the booksellers, to libraries, and literally gorge themselves with the “ologies” and “isms” of the day. Lord, Lord, how I enjoy meeting them at a musicale! There they sit, cocked and primed for a verbal encounter, waiting to knock the literary chip off their neighbor’s shoulder.

“Have you read “ begins some one and the chattering begins, furioso. ” Oh, Nietzsche ? why of course,”—“Tolstoi’s ‘What is Art?’ certainly, he ought to be electrocuted”—“Nordau? isn’t he terrible?” And the cacophonous conversational symphony rages, and when it is spent, the man who asked the question finishes:

“Have you read the notice of Rosenthal’s playing in the ‘Kölnische Zeitung?’” and there is a battery of suspicious looks directed towards him whilst murmurs arise, “What an uncultured man! To talk ‘shop’ like a regular musician!” The fact being that the man had read everything but was setting a trap for the vanity of these egregious persons. The newspapers, the managers and the artists before the public are to blame for this callow, shallow attempt at culture. We read that Rosenthal is a second Heine in conversation. That he spills epigrams at his meals and dribbles proverbs at the piano. He has committed all of Heine to memory and in the greenroom reads Sanscrit. Paderewski too, is profoundly something or other. Like Wagner he writes his own programmes—I mean plots for his operas. He is much given to reading Swinburne because some one once compared him to the bad, mad, sad, glad, fad poet of England, begad! As for Sauer, we hardly know where to begin. He writes blank verse tragedies and discusses Ibsen with his landlady. Pianists are now so intellectual that they forget to play the piano well.

Of course, Daddy Liszt began it all. He had read everything before he was twenty, and had embraced and renegaded from twenty religions. This volatile, versatile, vibratile, vivacious, vicious temperament of his has been copied by most modern pianists who have n’t brains enough to parse a sentence or play a Bach Invention. The Weimar crew all imitated Liszt’s style in octaves and hair dressing. I was there once, a sunny day in May, the hedges white with flowers and the air full of bock-bier. Ah, thronging memories of youth! I was slowly walking through a sun-smitten lane when a man on horse dashed by me, his face red with excitement, his beast covered with lather. He kept shouting “Make room for the master; make way for the master” and presently a venerable man with a purple nose—a Cyrano de Cognac nose—came towards me. He wore a monkish habit and on his head was a huge shovel-shaped hat, the sort affected by Don Basilio in “The Barber of Seville.”

“It must be Liszt or the devil!” I cried aloud and Liszt laughed, his warts growing purple, his whole expression being one of good-humor. He invited me to refreshment at the Czerny House, but I refused. During the time he stood talking to me a throng of young Liszts gathered about us. I call them “young Liszts” because they mimicked the old gentleman in an outrageous manner. They wore their hair on their shoulders, they sprinkled it with flour; they even went to such lengths as to paint purplish excrescences on their chins and brows. They wore semi-sacerdotal robes, they held their hands in the peculiar and affected style of Liszt, and they one and all wore shovel hats. When Liszt left me—we studied together with Czerny—they trooped after him, their garments ballooning in the breeze, and upon their silly faces was the devotion of a pet ape.

I mention this because I have never met a Liszt pupil since without recalling that day in Weimar. And when one plays I close my eyes and hear the frantic effort to copy Liszt’s bad touch and supple, sliding, treacherous technic. Liszt, you may not know, had a wretched touch. The old boy was conscious of it, for he told William Mason once, “Don’t copy my touch; it’s spoiled.” He had for so many years pounded and punched the keyboard that his tactile sensibility—is not that your new fangled expression?—had vanished. His “orchestral” playing was one of those pretty fables invented by hypnotized pupils like Amy Fay, Aus der Ohe, and other enthusiastic but not very critical persons. I remember well that Liszt, who was first and foremost a melodramatic actor, had a habit of striding to the instrument, sitting down in a magnificent manner and uplifting his big fists as if to annihilate the ivories. He was a master hypnotist, and like John L. Sullivan he had his adversary—the audience—conquered before he struck a blow. His glance was terrific, his “nerve” enormous. What he did afterward did not much matter. He usually accomplished a hard day’s threshing with those flail-like arms of his, and heavens how the poor piano objected to being taken for a barn-floor !

Touch! Why, Thalberg had the touch, a touch that Liszt secretly envied. In the famous Paris duel that followed the visits of the pair to Paris, Liszt was heard to a distinct disadvantage. He wrote articles about himself in the musical papers—a practice that his disciples have not failed to emulate—and in an article on Thalberg displayed his bad taste in abusing what he could not imitate. Oh yes, Liszt was a great thief. His piano music,—I mean his so-called original music,—is nothing but Chopin and water. His pyrotechnical effects are borrowed from Paganini and as soon as a new head popped up over the musical horizon, he helped himself to its hair. So in his piano music we find a conglomeration of other men’s ideas, other men’s figures. When he wrote for orchestra the hand is the hand of Liszt but the voice is that of Hector Berlioz. I never could quite see Liszt. He hung on to Chopin until the suspicious Pole got rid of him and then he strung after Wagner. I do not mean that Liszt was without merit but I do assert that he should have left the piano a piano and not tried to transform it to a miniature orchestra.

Let us consider some of his compositions.

Liszt began with machine-made fantasias on faded Italian operas—not however faded in his time. He devilled these as does the culinary artist the crab of commerce. He peppered and salted them and then giving for a background a real New Jersey thunderstorm, the concoction was served hot and smoking. Is it any wonder that as Mendelssohn relates, the Liszt audience always stood on the seats to watch him dance through the “Lucia” fantasia? Now every school girl jigs this fatuous stuff before she mounts her bicycle.

And the new critics, who never heard Thalberg, have the impertinence to flout him, to make merry at his fantasias. Just compare the “Don Juan” of Liszt and the “Don Juan” of Thalberg! See which is the more musical, the more pianistic. Liszt after running through the gamut of operatic extravagance began to paraphrase movements from Beethoven symphonies, bits of quartets, Wagner overtures and every nondescript thing he could lay his destructive hands on. How he maltreated the “Tannhäuser” overture we know from Josef Hofmann’s recent brilliant but ineffectual playing of it. Wagner, being formless and all orchestral color, loses everything by being transferred to the piano. Then, sighing for fresh fields, the rapacious Magyar seized the tender melodies of Schubert, Schumann, Franz and Brahms and forced them to the block. Need I tell you that their heads were ruthlessly chopped and hacked? A special art-form like the song that needs the co-operation of poetry is robbed of one-half its value in a piano transcription. By this time Liszt had evolved a style of his own, a style of shreds and patches from the raiment of other men. His style, like Joseph’s coat of many colors, appealed to pianists because of its factitious brilliancy. The cement of brilliancy Liszt always contrived to cover his most commonplace compositions with. He wrote etudes à la Chopin, clever I admit but for my taste his Opus One, which he afterwards dressed up into Twelve Etudes Transcendentales—listen to the big, boastful title !—is better than the furbished up later collection. His three concert studies are Chopin-ish; his “Waldesrauschen” is pretty but leads nowhere; his “Années des Pélerinage” sickly with sentimentalism; his Dante Sonata a horror; his B-minor Sonata a madman’s tale signifying froth and fury; his legendes, ballades, sonettes, Benedictions in out of the way places, all, all with choral attachments, are cheap, specious, artificial and insincere. Theatrical, Liszt was to a virtue and his continual worship of God in his music is for me monotonously blasphemous.

The Rhapsodies I reserve for the last. They are the nightmare curse of the pianist, with their rattle-trap harmonies, their helter-skelter melodies, their vulgarity and cheap bohemianism. They all begin in the church and end in the tavern. There is a fad just now for eating ill-cooked food and drinking sour Hungarian wine to the accompaniment of a wretched gypsy circus called a Czardas. Liszt’s rhapsodies irresistibly remind me of a cheap, tawdry, dirty table d’hôte, where evil-smelling dishes are put before you to be whisked away and replaced by evil-tasting messes. If Liszt be your god, why then, give me Czerny, or better still, a long walk in the woods, humming with nature’s rhythms. I think I’ll read “Walden” over again. Now do you think I am as amiable as I look ? Old Fogy.